The Lord of the Medieval Manor

Thursday 1st August Old documents can paint a surprisingly intimate picture of life in the past. We know, for instance, that Alice Carle, widow of Philip Carle, had to 'make and get ready litter for the lord’s bed and shall have a loaf, a gallon of ale and a dish of cooked food for her pains.'

Old documents can paint a surprisingly intimate picture of life in the past. We know, for instance, that Alice Carle, widow of Philip Carle, had to 'make and get ready litter for the lord’s bed and shall have a loaf, a gallon of ale and a dish of cooked food for her pains.'This little gem comes from a fourteenth century custumal, a custumal being a document which sets out the tasks to be performed, by custom, by each of the tenants of a manor.

Sadly, no custumal survives for Steyning itself but they do for a couple of our neighbouring manors. This example comes from Streatham, just the other side of the river, but we have also drawn on a Wiston custumal as well.

Having his bed prepared for him was not the only perk enjoyed by the lord of the manor. Everything was considered, so John Loteby had to 'clean out the buildings of the Manor once a year against the lord's coming, and shall gather reeds or rushes against his coming. He shall plant potherbs for two half days before or after dinner, and shall gather apples for two half days, before or after dinner. He shall carry the letters of the steward of the lands for summoning the Court.'

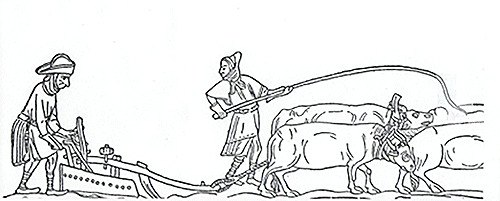

Moreover, Walter, son of Henry Pokerle, when the lord came in the summer, had to 'cart two wainloads of sticks to make bowers.' – though it’s a bit difficult to visualise what is meant by this. There was also William Marchal, the smith. Amongst various responsibilities for keeping the manor’s ploughs in good order, he had to 'shoe the steward's horse on four feet every time he holds Court, and shall have 1d. for the four shoes.'

The steward was responsible to the lord of the manor for all the manors in a particular lordship. Steyning was just one of the manors belonging to the Abbey of Fecamp and the Abbey’s steward would have divided his time between all of them.

When he attended the court sittings held in the manor of Steyning Walter Bennett, the steward for Fecamp in 1338, was himself referred to as ‘the lord’ in an old account roll: he was allocated one bushel of oats for his horse and, on various occasions, two piglets, a lamb, and three geese as court expenses plus 'four sheep for the Lord’s hunting dogs.'

Those further down the manorial hierarchy also did reasonably well. The ‘Reeve’, in Steyning’s case William de Saon, looked after the day to day running of the manor. Over in Streatham, that would have allowed him to have had 'a horse or mare on the lord’s pasture in summer, and in winter at hay without provender,' and 'his food as often, and as long as, the Lord is in the manor, and also when the steward comes to hold Court. In harvest, that is from Lammas (August 1st) to Michaelmas (September 29th), he shall have a quarter of barley, if the lord is not staying in the manor, and if he is he shall be at the lord’s table, if the lord wills.'

There was a ‘Rider’ too, whose job was to 'oversee that the reapers reap the lord's corn well and fairly'. He would 'have his food at three meals, and his horse likewise, and he shall have an aver [a carthorse] in the lord’s pasture in summer. He shall also have his dinner as long as the lord stays in the manor.'

It may be one of those coincidences that the ‘rider’ at Streatham in 1374 was Robert Wolgar and the man in the same roll in Steyning in 1338 was John Wolgar.

But the full extent of the lord’s control over his tenants is set out in his contract with one, William Holdene. 'If he dies' it says 'the lord shall have as a heriot his best beast, or 6d. if he have none. He shall not give his daughters in marriage, nor sell colts or steers bred by him, nor part with them in any way, nor put his son into Orders, without the lord's leave.' And yet this clause was written into the custumal at a time when the ties of lordship were beginning to loosen.