Museum Archives: No fence to sit on

Friday 1st April

‘In good King Charles’ golden days, when loyalty no harm meant, a zealous high churchman was I, and so I gained preferment’

In the early 1600’s Archbishop Bancroft was determined to rid parishes of puritan ministers. Stephen Vinall, vicar of Steyning, was one of these. The diocese of Chichester had already pressed their puritan vicars to ‘subscribe and conform to sutch articles, rites and ceremonies as are set down and established by his majesties said laws and ordinances’, but Vinall did not do so. In 1605 a new man, Jonas Michael – ‘a public preacher lawfully authorised’ was chosen to take over from him and it was agreed, as compensation for Vinall’s peremptory deprivation of his incumbency, to allow him to continue to occupy ‘the vicarage and its pasture ground’ for a further six months.

However, during those six months, Vinall reckoned that he had found a legal loophole and could claim that Michael’s incumbency was invalid and that the tithes and revenues due to the church should still be his. Writs and affidavits flew about and it was not far short of a year before Stephen Vinall finally left and Jonas Michael could enjoy his revenues and conduct services once again.

On Jonas Michael’s death in 1630, Leonard Stalman became the vicar and was soon having to deal with Archbishop Laud’s drive to enforce a strict ritualistic uniformity, incorporating some Catholic traditions, into the Church of England – a drive which was at odds with many strands of puritan belief.

On at least two occasions Stalman and his churchwardens were asked a whole raft of standardized questions to verify whether or not he conformed to Laud’s liturgy. Did he, for instance, abstain in his sermons from ‘those high points of speculation which have in several ages raised combustion in Christian Churches, forbidden by his sacred Majesty in his Declaration.’ To which the churchwardens’ answer was that ‘he meddleth not with high points of speculation’. In fact, in answering all 115 questions the churchwardens almost always echo the phraseology and sentiment of the questions.

If there was anything amiss – if he did not wear a surplice whilst conducting divine service, or did not wear a cassock whilst preaching, or failed to read the litany every Wednesday and Friday – they were not saying.

After twelve years as Steyning’s vicar, during which he had had to contend with the fall out from dreadful weather, desperate grain shortages and epidemics plus the more mundane needs of repairing and maintaining the fabric of the church, he was faced with a final challenge from the authorities. He was required to persuade the whole of his congregation (albeit, only the men) to sign a ‘Protestation’ against ‘the designs of the priests and Jesuits and other adherents of the see of Rome’ – and in support of ‘the true reformed Protestant religion’.

This, we guess, he would have been happy with though, this time, it was in support of ‘the power and privileges of Parliament’ rather than being in response to ‘his sacred Majesty’s Declaration’.

Perhaps he was content with that. He certainly endorsed Steyning’s ‘Protestation’ with the words ‘none hath refused’. But would he have been happy with putting his name to the ‘Solemn League and Covenant’ two years later? It called for the adoption of Presbyterianism and the abolition of bishops, but by then he had died and been succeeded by an outright Puritan, Robert Child, who had no qualms about doing so.

So, the pendulum had swung again. Fifty years before it had been puritan ministers who had been ‘deprived’. Now it was puritans in the ascendent and ‘Laudian’ ministers like Lawrence Davenport of Bramber who were listed to be deprived of their livings.

We suspect that this was a side of the fence on which Leonard Stalman would not have been happy to come down.

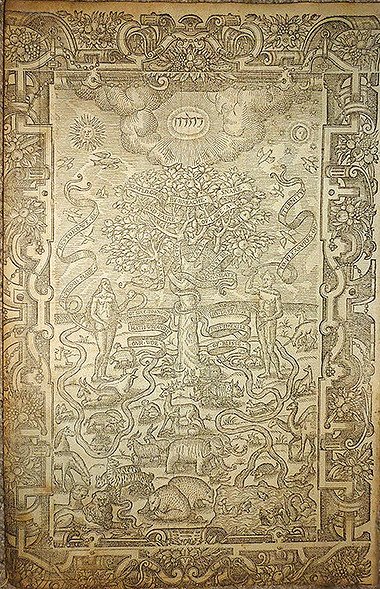

Above: The Breeches Bible was first published in full in England in 1576